Last year, the deadliest wildfire season in state history swept across California. More than 8,000 fires burned nearly two million acres and cost hundreds of millions of dollars to suppress.* In a matter of minutes, a town named Paradise was engulfed in flame and almost completely destroyed; 85 people died.

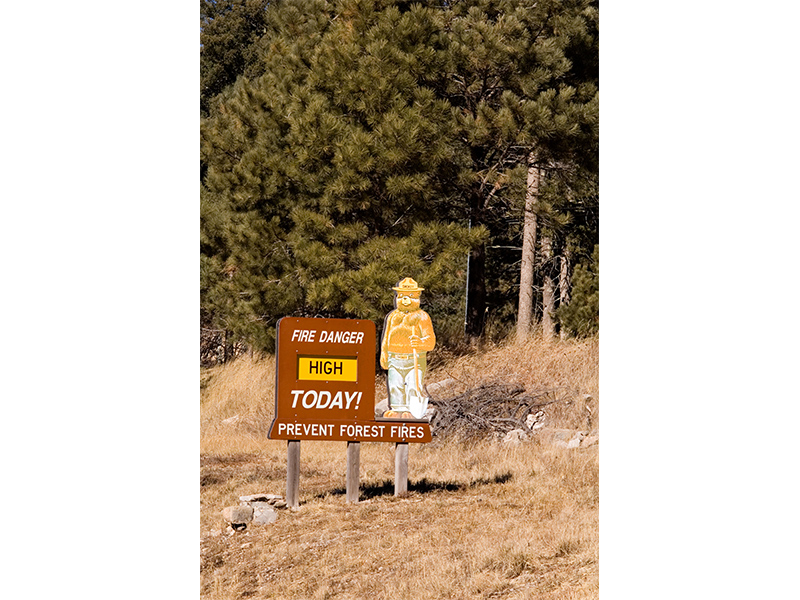

The United States had been living in fear of such devastation since the early years of World War II when fire was seen as a weapon of war. And for almost as long, we’ve had Smokey Bear, sweetly but insistently reminding each of us of our role in protecting the country from this danger: “Remember—only you can prevent forest fires.”

In 1942, Japanese submarines shelled an oil field outside Santa Barbara, near the 2,700-square-mile Los Padres National Forest. Concerned that fire on the homefront could distract from the war effort, the War Advertising Council and the U.S. Forest Service launched a campaign to raise public awareness of the threat. The early ads looked like many other wartime messages. “Another Enemy to Conquer: Forest Fires,” proclaimed a red stamp. “Our Carelessness: Their Secret Weapon,” said a poster with Hitler peering down on a blaze. Then Disney temporarily loaned Bambi—who had been introduced in 1942—to the effort, and the public started listening.

Inspired by the power of a charismatic cartoon, the War Advertising Council dreamed up Smokey in his ranger’s hat and dungarees. He first appeared in August 1944 pouring a bucket of water on a campfire saying, “Care will prevent 9 out of 10 fires.” In 1947, he got his better-known tagline.

Smokey was a sensation. In 1950, when a black bear cub was rescued from a burning forest in New Mexico, he was named Smokey and sent to Washington, D.C., where he lived at the National Zoo. (The Zoo is celebrating Smokey’s 75th with a special exhibit.) Two years later Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins, the songwriting team behind “Frosty the Snowman,” wrote an ode to Smokey. (Called “Smokey the Bear” to improve the rhythm, it led to decades of confusion over the character’s name.) And by 1964, Smokey was receiving so many letters from children that the post office gave him his own ZIP code; now he has an Instagram account and a Twitter feed, and he’s learned to speak Spanish. Today, the Ad Council estimates that 96 percent of adults recognize him—the sort of ratings usually reserved for Mickey Mouse and the president.

Smokey’s popularity made him an effective spokesbear for the Forest Service’s fire prevention message, which helped dramatically reduce fire on America’s public lands. Between the 1930s and 1950s, the average number of annual wildfires in the United States decreased by over 40,000. By 2011, the average number of acres burned by wildfire each year had dropped from 22 million in 1944 to just 6.6 million. Smokey “ties fire suppression to good citizenship,” explains Catriona Sandilands, an environmental studies professor at York University in Toronto. “With him, there is no question that fires are bad, and that individual citizens are responsible.”

But what if Smokey was actually wrong about that?

Some scientists now believe that the simple idea that fire is bad has made some forests more susceptible to flame—a phenomenon that they call the “Smokey Bear effect.” Areas where fires have been prevented for decades have simply been storing “fuel,” like underbrush growth and dead standing trees. Where the changing climate has brought drier conditions, this land is primed to spark easily. Now, a catastrophic blaze, once an unusual occurrence, could be set off by the heat from a lightning strike.

“The crisis is not the number of fires, it’s that we have too many bad fires and too few good fires,” warns Stephen Pyne of Arizona State University, a leading scholar of forest fire history. “It’s equally a problem that we’re not doing the good burning that would calm bad fires.” Smokey’s focus on fire prevention is dated, Pyne says.

Government policy has evolved to include the targeted use of controlled burns—“good burning”—in hopes of preventing larger, unplanned fires. And Smokey’s official motto changed subtly in 2001 to reflect this. Now he says, “Only you can prevent wildfires”—the idea being that forest fires can be lit and controlled, but wildfires can’t. “There is good fire and bad fire, that’s what his message is,” says Babete Anderson, a representative with the Forest Service. For kids, she explains, fire is birthday candles and campfires. Smokey’s message is “be careful with it. Make sure that your fire is dead out.”

But some fire-prevention experts think it’s impossible to separate Smokey from the old notion that it’s up to us to tame fire. “Let him retire with dignity,” Pyne suggests. The Forest Service has no plans to force out their 75-year-old mascot, who is also at the center of a merchandise industry. Still, Pyne dreams of a replacement.

Since 1947, Smokey has often been accompanied in posters by two cuddly cubs. In one image, they’re all holding hands: “Please folks,” Smokey says, holding his charges close, “be extra careful this year!” As Pyne sees it, “There’s two of them, so they could educate about lighting fires and fighting fires,” a modern understanding of fires, both good and bad. Smokey was created to speak to a generation shaped by fear of war. Those cubs could be a voice for a new generation learning to coexist with nature in an era of climate change.

When the federal government gets into cartooning, you know there's trouble

Research by Sonya Maynard